National Parks have been a staple of American culture, making up 84 million acres of the United States. The importance of natural landscapes and public spaces within society began with one intelligent and creative man: Frederick Law Olmsted. Over 150 years ago, Olmsted transformed how society thought about public spaces through his keen artistic eye. Throughout his life, the landscape architect designed and influenced over 100 public parks and grounds, most notably New York City’s Central Park, the U.S. Capitol Grounds, Prospect Park in Brooklyn, Biltmore Estate, Yosemite National Park, Buffalo Olmsted Parks Conservancy, Niagara Falls, and so many more. Olmsted’s fruitful list of accomplishments throughout his landscaping architectural career can be stemmed back to a young man visiting a beautiful park in England.

OLMSTED’S EARLY LIFE

Photo of Frederick Law Olmsted, 1857.

Olmsted was born in 1822 in Hartford, Connecticut. Whether being due to temporarily blindness at age 14, or because of his adventurous and eclectic nature, Olmsted left the formal education path at the age of 15 and became a self-taught career man. His young career journey was since filled with many different roles. He spent time at sea sailing to China as an apprentice, then worked on his father’s farm in Staten Island. Olmsted also had an early career in journalism, traveling throughout the American south publishing several newspaper reports. His travel bug and curiosity of the world can be largely attributed to his father, John Olmsted. Frederick’s father took his family to see many scenic landscapes, from Niagara Falls to Quebec and most of New England. Olmsted’s appreciation for landscapes reached new heights in 1850 when visiting Birkenhead Park in Liverpool, England. He was amazed not only by its design and details, but also that it was shared by all classes; Parks were usually reserved privately for wealthy class people on private estates or behind reserved gates. Margarete R. Harvey explains, “Here, Olmsted began to envision the possibility of shaping and tending the earth not only for its agricultural benefits and scenic potential, but also for the betterment of society”. This trip set Olmsted back to America on a new mission and a feeling of purpose.

“WHEN PARKS WERE RADICAL”

Central Park, NYC

Before Olmsted’s parks, the only public spaces people could go throughout America were graveyards. Having to play and find recreation within a cemetery expressed to Olmsted the profound need for public parks in cities. His determination for a better living environment led to his very first, and arguably most well-known, project: New York City’s Central Park. New York State Legislature approved of the Central Park project in 1853 and Olmsted, architect Calvert Vaux, and the Commissioners got to work. Central Park allowed Olmsted to tap into his topography, mapping, and agriculture skills while developing his scenic architectural eye. He learned a lot working alongside Vaux from his expertise about the fundamentals of design. At just the age of 36, Olmsted launched the largest public works program of their time. The design stretched out for 847 acres in the heart of New York City with an eye for natural and formalized symmetry. The bridges are intricately placed with architectural beauty and complimented the natural design of the park. Central park’s design allows for recreation for all pedestrians with enough space, walkways, shading and sites for everyone.

In 1865, he continued on to design Prospect Park with his partner Vaux in Brooklyn, New York, which was also a great success. This smaller park setting had a large reservoir in its center and was completed with its natural forests and rustic elements. Olmsted also made his mark with the country’s oldest system of parks and parkways in Buffalo, New York. The size of the project was the same as Central Park at 850 acres, but his design approach was entirely unique to his previous success. The Buffalo parks and parkways make up 24 pieces of greenery throughout, becoming the first interconnected urban park system in the United States.

The Biltmore Estate - Asheville, NC

Olmsted also contributed to the design of Vanderbilt’s property, the Biltmore Estate in 1888. The estate is 8,000 acres and full of formal and informal gardens in Asheville, North Carolina. There, he creates a personalized horticultural experience unlike any other, with over 4,000 plants and species planted throughout. Today, over a million people visit the Estate each year admiring the beautiful design by the creator of American Architectural Landscape. One of Olmsted’s principles with design is to create art that fits the landscape and doesn’t change its integrity and bones. His values also led him to preserving many areas for their natural beauty, like Niagara Falls on the Canadian border and Yosemite in California. He had the talent to recognize which places needed shaping and direction and which needed to be preserved and stand by themselves: to be left alone in their American landscape beauty.

OLMSTED’S LEGACY

Niagara Falls was an attraction that brought many tourists. In the mid 1800s, the attraction became overrun by ill-intentioned businessmen that did not take proper care of the landscape and often took advantage of the visitors. Olmsted was one of the people that fought for state officials and local governments to act and help better its Niagara Falls. The Falls were cleaned up thanks to him speaking up against the actions he saw. This situation showed Olmsted the potential disaster in overdevelopment and the importance of government protection in parks and landscapes. His influence stretched past landscapes and parks as well, with his movements to help improve sanitary living conditions within cities and his recognition of the impact of mental health. He served as General Secretary of the United States Sanitary Commission for 2 years. He dedicated his time to improving the sanitary conditions of army camps and soldiers. Then, when living in New York City, Olmsted saw the effect of the poor sanitary tenements in Lower Manhattan and its cause of the Great Fire of 1845. The debates caused the first tenement law to pass in the country, which controlled and regulated unhealthy housing conditions through better drainage of waste and outdoor latrines. Echoing his call to better living conditions, Olmsted argued that public parks will be the lungs of the urban age: helping clean the air and the hearts of the community within it.

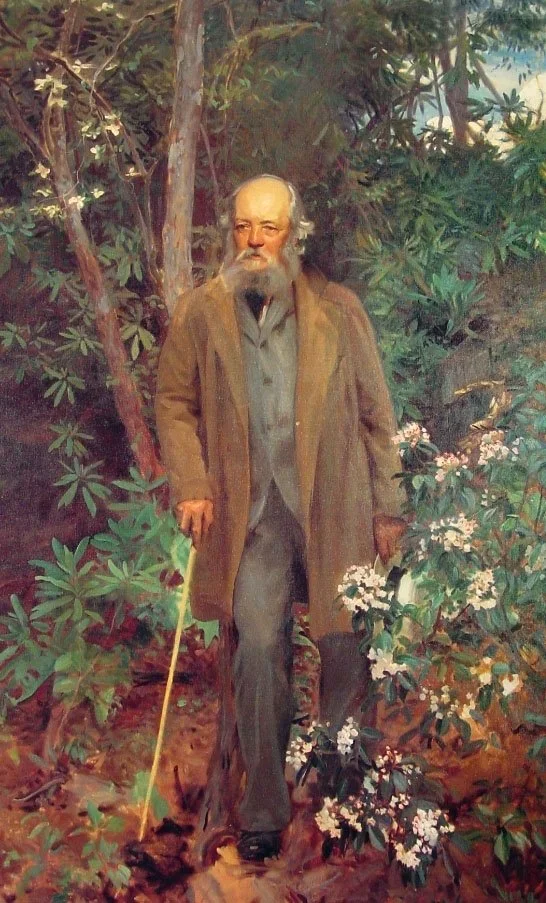

Frederick Law Olmsted, oil painting by John Singer Sargent, 1895.

Olmsted’s passion for his work was undeniable, as he worked constantly and slept very little throughout his career. His drive to push as much talent out of himself as possible showed how much he felt had to give to communities. Olmsted knew the gift possessed and was sure to express his passion as much as he could before his death. The acclaimed landscape architect passed on August of 1903 at the age of 81. He left behind four children and a permanent imprint on the country and world. “Today there are 417 park sites across the US covering over 84 million acres” (CBS). Olmsted opened society’s eyes to the beauty and necessity to harmonize urban life with parks and landscape. Olmsted believed a park should complement the city which it lives, while still remaining faithful to the natural terrain it belongs to.

With Olmsted’s 200th birthday coming this 2022, we ask you to go outside and appreciate nature. Spend time in your local parks and take note of its design: its pathways, the curves of the hills and placements of bridges and ponds. Visit one of Olmsted’s hundreds of landscapes throughout the country and experience the legacy he left for all its people. His designs go beyond parks and national sites, with private estates, suburbs, and college campuses as well. Olmsted lived a life that brought permanent beauty and influence throughout America from the 19th century on to modern-day, and for that we are forever grateful.

Author: Devin Gavigan